Mississippi in Context

Mississippi has executed twenty-three individuals since 1976. Another thirty-five are on death row. Six have been exonerated.

How does this compare to the rest of the United States? To the rest of the world?

Not all states impose the death penalty

There are twenty-seven states that use capital punishment. Some of these states, like California, have capital punishment on the books but have placed a moratorium on executions.

Learn which states use capital punishment at Death Penalty Information Center’s state-by-state page.

The death penalty wasn’t always legal

The United States Supreme Court struck down death as a sentence in 1972’s Furman v. Georgia. This reprieve didn’t last long, as the Court decided capital punishment was allowable in 1976’s Gregg v. Georgia.

Death sentencing rates are trending down

Death sentencing rates have dropped by around 80% since the late 1990s. Mississippi’s rate, .035%, remains above the national average of .022%.

See a state-by-state breakdown of sentencing rates at Death Penalty Information Center’s Death Sentencing Rate by State page.

Image via Portland Mercury

Not many crimes are punishable by death in Mississippi. Only treason and murder with one or more of ten specific aggravating circumstances qualify an individual to be sentenced to death.

Read Mississippi Code Title 99 for a full list of death penalty warranting circumstances.

Mississippi’s post-1976 execution rate is lower than many other southern states, including Florida (103), Georgia (76), Alabama (70), both Carolinas (43), and Louisana (28).

There have been fifty-nine “well-known” botched executions since 1976. Of those, only one has occurred in Mississippi - Jimmy Lee Gray’s 1983 execution by gas chamber.

Read Marian J. Borg’s and Michael L. Radelet’s “On botched executions” for more information on what defines a botched execution.

With lethal injection drugs becoming difficult for states to obtain, some have chosen to reinstate older methods of execution. In 2022, Mississippi joined South Carolina, Oklahoma, and Utah in allowing prisoners to be executed via firing squad.

See graphs on which methods are legal in which states at NPR.

How Mississippi compares to other states in numbers of individuals executed post-1976. Add 2022 and 2023 numbers to the listed total to get the current number.

Race plays a large role in death sentences

53% of death row inmates are Black or Hispanic, despite the fact that, combined, they only account for 31% of the population.

Read more about race and death sentencing at the National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers’ Race and the Death Penalty Page.

The race of murder victims also plays a role

Death Penalty Information Center’s data shows that “more than 75% of the murder victims in cases resulting in an execution were white, even though nationally only 50% of murder victims generally are white” (“Facts About the Death Penalty”).

Mississippi death row demographics

Mississippi’s death row reflects this racial disparity. There are currently twenty-one Black individuals on death row, twelve White individuals, one Spanish or Hispanic individual, and one Asian individual. Of those executed between 1983 and 2022, however, only six were Black, while seventeen were white.

Mississippi Department of Corrections lists racial demographic information on their Current Death Row Demographics page.

The death penalty is largely outlawed in the rest of the world. Including the United States, only twenty-four countries punish prisoners by death. Of these, China executes the most individuals, with Iran, Saudi Arabia, Egypt, and the United States performing the vast majority of remaining executions.

Read Amnesty International’s page on the death penalty for detailed information and mapping of international executions.

Although death sentencing and execution rates are decreasing in the United States, they are rising worldwide. There were 1,998 death sentences in 2016, 3,117 in 2016, 2,591 in 2017, 2,531 in 2018, 2,307 in 2019, 1,477 in 2020 2,052 in 2021, and 2,016 in 2022. These numbers only reflect known sentences. The true numbers are likely higher.

Statistics via Amnesty International’s “Executions and death sentences recorded globally (2015 - 2022)” found on their death penalty page.

There are four international treaties of different scopes that aim to abolish the death penalty both worldwide and regionally. These are the Second Optional Protocol to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, the Protocol to the American Convention on Human Rights, Protocol No. 6 to the European Convention on Human Rights, and Protocol No. 13 to the European Convention on Human Rights.

There have been 163 executions of individuals under 18 years old between 1990 and today. These executions took place across ten total countries: China, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Iran, Nigeria, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, South Sudan, Sudan, the USA and Yemen.

For more information, see Amnesty International’s 2002 report on juvenile executions and their 2022 report on “Executions of persons who were children at the time of the offence 1990 – 2021”

Murder rates in death penalty vs. non-death penalty states since 1990.

Graph via Death Penalty Information Center.

Capital punishment for minors is illegal

The 2005 Supreme Court case Roper v. Simmons made it illegal for someone to be sentenced to death for a crime committed when they were under eighteen years of age. Between 1976’s reinstatement of the death penalty and 2005, twenty-two people were executed for crimes committed when they were minors. Post-2005, seventy-two individuals on death row received re-sentencing.

Read Capital Punishment in Context’s page on the death penalty for juveniles for more information on underage sentencing.

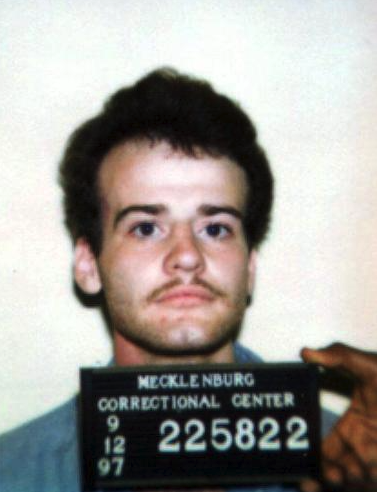

The youngest person executed was 23

Before 2005’s Roper V. Simmons, the youngest person executed for crimes committed when underage was Steve Edward Roach. Roach was convicted of murder and sentenced to death when he was 17 years old. After five years of appeals, he was executed at the age of 23.

See Amnesty International’s 1999 call for support for Roach.

Raising the minimum death sentence age

There is a growing movement to raise the minimum age at which someone can receive a death sentence from 18 to 21. Based on evolving understanding of how young adult brains form and function, this movement notes that individuals under 21 already have certain freedoms restricted, such as the ability to buy alcohol, because of their age.

The N.Y.U. Review of Law & Social Change recently published the article “A Decent Proposal: Exempting Eighteen- to Twenty-Year-Olds From the Death Penalty” which draws out this argument.

Steve Edward Roach was executed in 2000 when he was 23 years old. Image via Virginia Department of Corrections.

Daryl Atkins, whose 2002 case made the death penalty illegal for individuals with an intellectual disability. Image via Lady (Legal) Writer.

The 2002 Supreme Court case Atkins V. Virginia made it illegal for individuals who are intellectually disabled to receive the death sentence.

Learn more about Atkins V. Virginia.

Despite the Supreme Court’s ruling, many individuals who qualify as intellectually disabled have been executed, including, his defense argued, Earl Berry.

There is not a single national definition of what constitutes an intellectual disability. The common consensus, including twelve states’ capital punishment sentencing guidelines, is an IQ below 70.

The Innocence Project explores intellectual disability and state-by-state approaches through the case of Purvis Payune.

57% of individuals in Mississippi who were facing the death sentence have received lesser sentencing due to claims of intellectual disability.

See Death Penalty Information Center’s review of John Blume’s nationwide study on intellectual disability and death penalty sentencing for more information.

Year-by-year breakdown of individuals executed in Mississippi

Mississippi executed 332 people pre-1972

Mississippi began executing individuals as far back as 1804, some thirteen years before it become a state. The vast majority of these executions (238) occurred via hanging.

Data collected via Death Penalty Information Center’s ESPY File which tracks executions in the United States back to 1608.

Most executions were of Black men

Of all individuals executed before 1972’s Ferman V. Georgia, 272 were black, seventy were white, eight were unknown, and one was Native American. Likewise, 344 of those executed pre-1972 were male, five were female, and two were unknown. The oldest person executed was Jeff Wallace, a white man hanged in 1926 when he was 70. The youngest individuals executed were several 17-year-olds.

Data collected via Death Penalty Information Center’s ESPY File.

History of botched executions

Guy Fairley was executed by hanging in 1932. His botched execution inspired public outrage and led to the 1940 construction of Mississippi’s portable electric chair. The state’s method of execution had changed to the gas chamber by 1955, though the first individual executed by lethal gas, Gerald Gallego, suffered for more than forty-five minutes before dying.

Read former Superintendent of Mississippi State Penitentiary Donald Cabana’s “The History of Capital Punishment in Mississippi: An Overview” for additional historical context.

Image via McCain Library’s “Preparations for the public hanging of Will Mack; 23 July 1909”

Image via the Equal Justice Initiative’s Museum and Memorial brochure.

Mississippi has a long history of extra-legal lynchings. According to Mississippiencylopedia.org, “Lynchings took place in rural areas of Mississippi as well as in cities such as Hattiesburg, Meridian, and Natchez. Because lynchings were not recorded until the 1890s, the real number of victims will never be known. Conservative estimates put the number at 476 victims (including 24 whites) in Mississippi between 1889 and 1945—almost 13 percent of the 3,786 lynchings in the United States during that period and the highest total of any state.”

Read the entire “Lynching and Mob Violence” entry.

Terence Finnegan’s A Deed So Accursed: Lynching in Mississippi and South Carolina, 1881–1940 explores both legal and extra-legal lynchings in Mississippi and South Carolina. The Mississippi lynchings he studies and contextualizes include the 1919 extra-legal lynching of John Hartfield in Ellisville.

The Equal Justice Initiative, founded in 1989 by Bryan Stevenson, operates both the National Memorial for Peace and Justice and The Legacy Museum: From Enslavement to Mass Incarceration. These projects document the centuries-long terror of extra-legal lynching, and violence, against people of color in the American South.

The EJI’s resource page includes reports on racial violence and curricula for teaching.

The National Parks Conservation Association wants to create a national park in response to the 1955 lynching of Emmett Till.

Read Kate Siber’s essay on Mississippi’s history of extra-legal racial violence.